Fixed term parliaments are a good thing. Let's get that out of the way. Obviously it's depressing when you're looking ahead to a long and guaranteed stretch with a rabidly free-market government, but it's just the price the country pays for

voting Lib Dem the levelling of the playing field and the removal of this curious power of the Prime Minister to pick the day that suits him best.

Just imagine if George Bush had been able to hang on longer, and let McCain fight an election once the economic crisis had reached a more favourable point. No, just as at Holyrood, let Westminster please have fixed terms.

Having said that, there are some serious problems. First, it is too long, and longer than most (see

UCL's Constitution Unit on this). I'm in favour of more democracy, more chances for the people to kick the bums out, and even the old five year maximum felt less like a

trap than a fixed five year session.

Next, and more seriously, the point when it's scheduled to end is simply wrong. The Tories might not have realised that the first Thursday in May 2015 is also a Holyrood election day, but the Lib Dems with their Scottish contingent surely did. A five year "first Thursday in May" would clash with Holyrood every 20 years. Even if you had to have five year terms, why that one day?

It's been put to me that this is an "oh shit" moment for the Lib Dems in retrospect, but I don't buy that. Their chief negotiator and now occupant of the role the SNP used to call Governor General, Danny Alexander,

knows only one thing - politics. Even as an MP rather than an MSP, the next Holyrood election dates are presumably the first things he scratches into the long-term planner at the front of his diary each year, precisely because they are already fixed.

The proposed simultaneous elections would cause serious difficulties in Scotland.

As Sev Carrell points out, there will be potentially many different votes that same day, including those for smaller first past the post constituencies for Holyrood and larger Alternative Vote constituencies for Westminster.

There are other problems, too, ones we already know about. In 2007 we had a Holyrood election with a

rigged ballot paper on the same day as local elections carried out under Single Transferrable Vote for the first time, and the country paid another price.

Contrary to predictions, the spoilt papers weren't for the locals, and the public appeared to adjust very quickly to expressing more complex preferences - after all, most folk know what their second preference is, and who should be put last. The ballot caused problems for Holyrood, but that's not the issue here either.

The problem was the campaign. Local issues got no airing at all. They were completely buried under Holyrood coverage. No-one cared enough to discuss who would run our Councils. The media were all fascinated by the can-he, can't-he story of Salmond's return. But it matters - we have been left with some disastrous local government across Scotland, notably those rudderless SNP/Lib Dem coalitions.

The same would apply in spades in 2015 if this plan goes ahead, and Holyrood would just be an afterthought. Even the Scottish media would be obsessed with the judgement to be passed on the Cameron-Clegg coalition, should it actually survive that long. This neglect of devolved issues simply cannot be allowed to happen.

Which leads us to the next issue, the 55% rule. As originally billed on Twitter, it was a 55% threshold for votes of no confidence, which would clearly be wrong. Then we heard it was 55% for both confidence votes and dissolution. Now it's definitely for dissolution but probably not for confidence votes.

No government can or should survive if a majority of the Parliament has no confidence in it. But the

frantic Lib Dem bloggers have a point too: in a Parliament of minorities, there's no absolute need for an immediate election just because a government falls.

Imagine Dave Cameron himself is caught fiddling the books but won't step down. The Lib Dems might find themselves voting down his government but backing one led by, say, William Hague.

Or if Labour had won a few more seats there would have been nothing unconstitutional about the junior partner deciding to switch to them mid-term. That unstable rainbow could again be attempted. But the rainbow couldn't trigger an election at the point of maximum Tory weakness. This is the kind of scenario

considered so admirably by Love & Garbage today. The buttons really help.

Plus, as many have observed, Holyrood has a similar rule, with a higher threshold of two thirds. 86 MSPs are required to vote for an early election here. So the 55% is even more democratic, right, and more stable too?

Wrong.

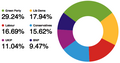

First,

as Lib Dem MP Andrew Stunnell admits, the level is set at 55% based on the results last week. As the non-Tories hold 52.8% of the seats (including Sinn Fein), this level was designed for, and is fit only for, the current breakdown of the Commons. Next Left have

gone to town on this, and they're right. Some of the Lib Dem defences of it are truly absurd (see

this from perhaps their most petty blogger).

Holyrood's two thirds super-majority was agreed before anyone knew what the results were, and not built for any one party's (or two parties') interests. Should we really make quasi-constitutional law based on the outcome last week?

Moving neatly on again, that brings me to the crux. There remains no codified constitution for Westminster, which is why this can't work. Imagine only 52.8% of MPs think a dissolution should happen. They can just pass a law overturning the 55% rule by simple majority, and it's game over for Dave.

Then it'd need to get through the Lords. What Lords are those? The

current Lords, the

interim proposed Lords stuffed full of Tories and Lib Dems, or the post-reform Lords perhaps elected by proportional representation?

Even if any House of Lords, however constituted, opposes the Immediate Election Bill, this 55% threshold wasn't in anyone's manifesto, so there's no constitutional reason why the

Parliament Act couldn't be used by the rebellious but slim majority to force it through. The Acts talk about the relationship between the Commons and the Lords, not the government and the Lords. Result: election, albeit messily delivered.

And here's another difference with Holyrood. No number of MSPs can change the Scotland Act. Not even all 129 of them all acting together. It's effectively our constitution, and it can unfortunately only be changed at Westminster.

Whereas Westminster has no proper constitution (as the anoraks know, we do have one,

it's just uncodified). If it had one, with terms and conditions for amending it like any grown-up democracy, a rule of this sort could and should be introduced. But the level wouldn't be set at 55% and it certainly wouldn't be done in isolation from any reforms to the voting system, to party funding, or to the second Chamber (as an aside: please let this not be called the Senate in the end).

In short, we need a proper British constitution, only for amendment by the people, and set up through a Constitutional Convention. Without that, this move is empty and cynical tinkering and it will not work.

Every time you think the Lib Dems can't sink any lower, they manage it, on cuts, on electoral reform, on privatisation. Today it's energy. Here's Chris Huhne from 2007:

Every time you think the Lib Dems can't sink any lower, they manage it, on cuts, on electoral reform, on privatisation. Today it's energy. Here's Chris Huhne from 2007: